Inhabited Earth - “The People Planet”

Man and the Environment - The importance of human interaction with global environmental systems is becoming ever more apparent. To better understanding this relationship historically, at present and for the future, numerical models are a most useful tool when supported by geological and historical data. These models span a spectrum of scale and complexity, and can be used to determine the co-evolution of environmental and socio-economic conditions may shed light on the political consequences of present and future environmental change. Industry poses for the canonical mug shot for polluting the environment, and indeed there have been cases in which factories spewed harmful materials. One example is that of NJ Zinc, who operated a Zinc smelter in Palmerton, PA for about a century, before closing up shop. In the meantime, it deposited various metals throughout the region. Concern over the contamination of soils in the area may have retarded the town’s ability to recover economically from the closing of the smelter, but after analysis of the soils in the surrounding area, it appears that it is by now basically all within EPA standards for residential soils. Where did the metals go? The arsenic, cadmium, lead, zinc? Various processes can leach metals into the deeper soil, groundwater, and into rivers (Lehigh River, in this case). A complete historical analysis of the fate of the deposited metals has yet to be conducted. One of the most critical industries globally (and locally) is that of energy production. Electricity can be generated by burning coal (and boiling water to steam to drive turbines attached to generators), and we have lots of coal to burn. However, in addition to heat, coal-burning produces sulfur compounds, fly ash, bottom ash, and various “coal combustion residuals” (CCR) that have to be dealt with in the environment. These materials, can, however beneficially reused. The sulfur is scrubbed out using lime to make gypsum which is used to make wallboard used in all buildings. Very useful. The fly ash is actually an excellent pozollan for the production of cement and concrete. In response to a fly ash “spill” in Tennessee, where the ash was impounded behind a pile of more fly ash (not cement), and it failed, EPA considered declaring all CCR as hazardous waste (special waste), unless it was beneficially reused. The idea was that if it was expensive for power plants to send their CCR to hazardous waste facilities, they might use more for beneficial uses like gypsum and cement. Meanwhile, the beneficial reuse companies said that if the stuff they used were branded as hazardous under any conditions, they would stop using it at all. In any case, a simple calculation made by my student in the Energy Systems Engineering program determined that even if beneficial reuse increased until ALL wallboard was made from CCR, and ALL cement and concrete used as much fly as as physically possible, the remaining CCR shipped to the existing hazardous waste facilities throughout the US would fill them all up to capacity in 3 to 7 months, rather than the 40 years they are designed for. In the end, the EPA did not declare CCR as hazardous waste.

Man and the Environment - The importance of human interaction with global environmental systems is becoming ever more apparent. To better understanding this relationship historically, at present and for the future, numerical models are a most useful tool when supported by geological and historical data. These models span a spectrum of scale and complexity, and can be used to determine the co-evolution of environmental and socio-economic conditions may shed light on the political consequences of present and future environmental change. Industry poses for the canonical mug shot for polluting the environment, and indeed there have been cases in which factories spewed harmful materials. One example is that of NJ Zinc, who operated a Zinc smelter in Palmerton, PA for about a century, before closing up shop. In the meantime, it deposited various metals throughout the region. Concern over the contamination of soils in the area may have retarded the town’s ability to recover economically from the closing of the smelter, but after analysis of the soils in the surrounding area, it appears that it is by now basically all within EPA standards for residential soils. Where did the metals go? The arsenic, cadmium, lead, zinc? Various processes can leach metals into the deeper soil, groundwater, and into rivers (Lehigh River, in this case). A complete historical analysis of the fate of the deposited metals has yet to be conducted. One of the most critical industries globally (and locally) is that of energy production. Electricity can be generated by burning coal (and boiling water to steam to drive turbines attached to generators), and we have lots of coal to burn. However, in addition to heat, coal-burning produces sulfur compounds, fly ash, bottom ash, and various “coal combustion residuals” (CCR) that have to be dealt with in the environment. These materials, can, however beneficially reused. The sulfur is scrubbed out using lime to make gypsum which is used to make wallboard used in all buildings. Very useful. The fly ash is actually an excellent pozollan for the production of cement and concrete. In response to a fly ash “spill” in Tennessee, where the ash was impounded behind a pile of more fly ash (not cement), and it failed, EPA considered declaring all CCR as hazardous waste (special waste), unless it was beneficially reused. The idea was that if it was expensive for power plants to send their CCR to hazardous waste facilities, they might use more for beneficial uses like gypsum and cement. Meanwhile, the beneficial reuse companies said that if the stuff they used were branded as hazardous under any conditions, they would stop using it at all. In any case, a simple calculation made by my student in the Energy Systems Engineering program determined that even if beneficial reuse increased until ALL wallboard was made from CCR, and ALL cement and concrete used as much fly as as physically possible, the remaining CCR shipped to the existing hazardous waste facilities throughout the US would fill them all up to capacity in 3 to 7 months, rather than the 40 years they are designed for. In the end, the EPA did not declare CCR as hazardous waste.

COVID, Race, Environment and Health Inequities - Long-standing income and wealth disparities among ethnic groups and socioeconomic classes have come to the fore with the emergence of COVID-19. The pandemic has highlighted how minorities in many urban settings are disproportionately impacted by public health crises. Hispanic and African-American populations have been dying of COVID at twice the rate as other Americans. WHY? The pandemic presents an opportunity to study public health and environmental inequalities that result from perturbed, rather than typical, economic and social factors that exacerbate existing inequalities. We are conducting an initial study of how social variables such as race, ethnic origin and socioeconomic class interact with environmental factors such as air quality to shape health outcomes. The overarching goal is to answer, “How have social, political and environmental conditions led to public health inequities and associated disproportionate impacts from major health crises such as COVID-19, and how can an inequitable environment be expected to evolve in the face of changing climate, health care systems and political landscapes?” The initial focus is to measure the association between COVID-19 morbidity/mortality (for which data are readily available) and air quality, which is commonly degraded in urban areas. While air quality is easier to measure than other environmental media to which people in urban environments are also disproportionately exposed, it is likely that there exist multiple other stressors such as poor water quality, nutrition, and access to preventive medical care that impact the health of the urban poor, and that these may be further exacerbated by degraded air quality. Thus, studying the interaction between air quality, COVID-19 incidence and impact on health outcomes is meant to act as an initial point of study into a broader set of social and environmental variables and evolving relationships. Our ultimate goal is to provide insights for decisions makers to help resolve social, economic and health inequities prevalent in minority urban neighborhoods that may be exacerbated by pandemic impacts.

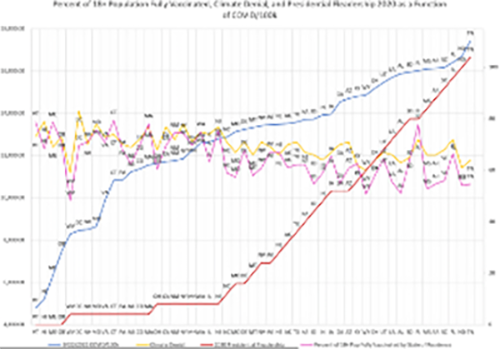

COVID, Race, Environment and Health Inequities - Long-standing income and wealth disparities among ethnic groups and socioeconomic classes have come to the fore with the emergence of COVID-19. The pandemic has highlighted how minorities in many urban settings are disproportionately impacted by public health crises. Hispanic and African-American populations have been dying of COVID at twice the rate as other Americans. WHY? The pandemic presents an opportunity to study public health and environmental inequalities that result from perturbed, rather than typical, economic and social factors that exacerbate existing inequalities. We are conducting an initial study of how social variables such as race, ethnic origin and socioeconomic class interact with environmental factors such as air quality to shape health outcomes. The overarching goal is to answer, “How have social, political and environmental conditions led to public health inequities and associated disproportionate impacts from major health crises such as COVID-19, and how can an inequitable environment be expected to evolve in the face of changing climate, health care systems and political landscapes?” The initial focus is to measure the association between COVID-19 morbidity/mortality (for which data are readily available) and air quality, which is commonly degraded in urban areas. While air quality is easier to measure than other environmental media to which people in urban environments are also disproportionately exposed, it is likely that there exist multiple other stressors such as poor water quality, nutrition, and access to preventive medical care that impact the health of the urban poor, and that these may be further exacerbated by degraded air quality. Thus, studying the interaction between air quality, COVID-19 incidence and impact on health outcomes is meant to act as an initial point of study into a broader set of social and environmental variables and evolving relationships. Our ultimate goal is to provide insights for decisions makers to help resolve social, economic and health inequities prevalent in minority urban neighborhoods that may be exacerbated by pandemic impacts. Climate Denial, COVID-19, and the Evolving Politics of Gender - The increasing role of women in leadership roles may be both a cause and effect of public attitudes. Recent politicization of science amidst increasing polarization of American politics juxtaposed with examples of female leadership (Fleadership) throughout the U.S (and abroad) begs the question of how understanding of science impacts crisis response decision-making in light of gender and political associations. Here, we compare at the U.S. state level, female gubernatorial leadership and presidential (and VP) voting patterns in 2016 and 2020 against climate denial, COVID-19/100k, and vaccination rates. Our findings demonstrate strong correlations between climate denial, high COVID-19/100k, low vaccination, and the 2016 and 2020 presidential votes for exclusively male candidates. Americans who embraced federal Fleadership in 2016 and again in 2020 were less likely to deny climate change and spread COVID-19. However, this has also been closely aligned with political partisanship. Fleadership had historically been mostly limited to Democratic slates, but with more Fleadership nationally, the gender-party bias is weakening. Our results suggest that rather than Fleadership inspiring responsible COVID-19 preventative behavior at state or national levels, or leading to better understanding of climate change, the populations who previously tended to elect females, also understand science more than those who do not. This further relates to the public acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines at the state level. The states with greater COVID-19 incidence and climate denial, also have the least fraction vaccinated. The state-wide variability in acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccines aligns with the correlations between climate change denial, COVID-19 infections, and Fleadership. These relations highlight the connections between health, climate and lack of public understanding of science, and thus the importance of science education at all levels throughout the population. The absence of effective climate policy on a national level may in part reflect the tensions between populations with contrasting science education and resulting actions.

Climate Denial, COVID-19, and the Evolving Politics of Gender - The increasing role of women in leadership roles may be both a cause and effect of public attitudes. Recent politicization of science amidst increasing polarization of American politics juxtaposed with examples of female leadership (Fleadership) throughout the U.S (and abroad) begs the question of how understanding of science impacts crisis response decision-making in light of gender and political associations. Here, we compare at the U.S. state level, female gubernatorial leadership and presidential (and VP) voting patterns in 2016 and 2020 against climate denial, COVID-19/100k, and vaccination rates. Our findings demonstrate strong correlations between climate denial, high COVID-19/100k, low vaccination, and the 2016 and 2020 presidential votes for exclusively male candidates. Americans who embraced federal Fleadership in 2016 and again in 2020 were less likely to deny climate change and spread COVID-19. However, this has also been closely aligned with political partisanship. Fleadership had historically been mostly limited to Democratic slates, but with more Fleadership nationally, the gender-party bias is weakening. Our results suggest that rather than Fleadership inspiring responsible COVID-19 preventative behavior at state or national levels, or leading to better understanding of climate change, the populations who previously tended to elect females, also understand science more than those who do not. This further relates to the public acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines at the state level. The states with greater COVID-19 incidence and climate denial, also have the least fraction vaccinated. The state-wide variability in acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccines aligns with the correlations between climate change denial, COVID-19 infections, and Fleadership. These relations highlight the connections between health, climate and lack of public understanding of science, and thus the importance of science education at all levels throughout the population. The absence of effective climate policy on a national level may in part reflect the tensions between populations with contrasting science education and resulting actions.